Where worlds collide - an interview with Noémia Prada - photographer and digital artist

Born in 1969 in Portugal, Noémia Prada is photographer and digital artist, blending emotion, technology, and dream into art. With a background in journalism, illustration, painting, and photography, and academic training in Communication Sciences and Sociology, her practice is grounded in photographic language and attentive to narrative, composition, and visual meaning. Having lived and worked for many years abroad across Europe, Africa, and the United States, her perspective has been shaped by cultural displacement and diverse human contexts. Now based in Portugal, she works through carefully curated visual series rather than isolated images, exploring emotion, memory, identity, and the human condition while maintaining a consistent authorial voice at the intersection of human experience and contemporary digital processes.

Background & Transition

You come from a deep photographic background — what was the moment when you first realised AI could become part of your visual language rather than a threat to it?

My background is not limited to photography; it also includes painting and journalism. All these languages coexist and influence one another in my work, and I use them together as part of who I am as an artist. Photography, for me, wasn’t just as a technical practice, but as a way of seeing. A way of framing, waiting, and believing in the world.

For a long time, my photographic practice was tied to presence: being there, witnessing, responding to what reality offered — or creating my own reality. I worked intensely, and still do, in street photography, however it was in studio work that I could truly give myself to my projects and to the ideas and concepts I wanted to develop.

The shift toward AI happened quietly and gradually. It was not abrupt. My first attempts with AI were honestly very poor. They were full of commonplaces and photographic stereotypes. I was creating images, but I was not satisfied with them, because they brought nothing new. They felt like more of the same — images very similar to what I was already seeing other photographers produce, and that was not what I wanted.

With practice, experience, and trial and error, I understood that I needed to find in AI something aligned with what I had always done and with my own vision. The images had to carry my obsessions and fears: childhood, old age, innocence, loss, memory, humanity, silence, the past, hope, pain, grief.

That was when I understood that AI was not an end in itself. It was a way for me to translate my vision of the world and of my inner world.

Do you see your AI-generated images as an extension of photography, a new medium entirely, or something that sits uncomfortably between the two?

I don’t see my AI-created images as something separate from my photography, nor detached from it. They exist in a fertile space between two mediums. They share the same visual language I have always worked with: composition, light, realism, emotion, and framing. AI isn’t a threat; it’s more of a challenge.

AI does not replace photography for me. It allows me to go further than what I was already doing. Many people ask why, I as a photographer, also work with AI. The answer is simple: it is precisely because I know how to photograph that I can work with AI.

Someone who does not understand photographic language, who does not have that background or something meaningful to express, will not truly create with AI. The work becomes disconnected from reality. I know that being a strong photographer allows me to be a strong digital artist, and that background is essential.

How does your experience behind the camera influence the way you “see” when you’re no longer physically present at the moment of capture?

Even when I am no longer physically present at the moment of capture, my photographic experience informs all my work. I think as a photographer and I work as a photographer — and that is what allows me to create what I create. I am documenting reality in terms of values, ideas, and vision, through two different but connected ways of working.

For me, coherence, cohesion, and consistency are fundamental. Without them, you can’t create a meaningful body of work.

At the end, I see myself as an artist who uses technology, imagination, dream and emotion to transform vision into art.

Process & Craft

Can you walk us through your process from initial idea to final image — where does authorship really begin for you?

For me, authorship begins long before any image is created. It starts with an idea, a feeling, a memory, or an inner tension that I need to explore. The tool comes later.

The process usually begins with a clear intention — something I want to say, question, or revisit. AI is part of that process, but it is never the starting point. What matters to me is coherence between the idea, the image, and what I want to express. Without that, there is no authorship, regardless of the medium.

What aspects of traditional photography (lighting, composition, lens behaviour, imperfections) do you consciously recreate or control when working with AI?

I work with the same elements I have always worked with in photography: composition, light, framing, realism, and emotion. These are not technical choices for me, they are part of how I think and see.

I pay a lot of attention to realism and to small imperfections. I avoid images that feel too clean, too polished, or artificial. I want the image to feel believable and human, because that is where emotion exists.

What interests me is not perfection, but balance — between control and fragility, between intention and accident.

What aspects of traditional photography (lighting, composition, lens behaviour, imperfections) do you consciously recreate or control when working with AI?

I work with the same elements I have always worked with in photography: composition, light, framing, realism, and emotion. These are not technical choices for me, they are part of how I think and see.

I pay a lot of attention to realism and to small imperfections. I avoid images that feel too clean, too polished, or artificial. I want the image to feel believable and human, because that is where emotion exists.

What interests me is not perfection, but balance — between control and fragility, between intention and accident.

How much of the final image is planning versus discovery — are you directing the image, or collaborating with the system?

There is always planning, because I start with a clear vision. But there is also discovery. I don’t see the process as pure control, nor as something left entirely to the system.

I guide the image, but I allow space for what emerges along the way. AI can surprise me, resist, or take the image somewhere unexpected. When that happens, I respond to it.

For me, it is a form of collaboration. The image is built through intention, dialogue, and adjustment, not through total control.

Do you ever intentionally introduce flaws or unpredictability to prevent the work from feeling too polished or artificial?

Yes, very consciously. I am not interested in perfection. I often reject images that feel too clean or too resolved.

Imperfection is important to me. It creates tension, discomfort, and humanity. Without that, the image becomes decorative and loses its emotional truth.

Reality, Truth & Perception

Your images feel convincingly real — what role does believability play in your work, and where do you draw the line between realism and deception?

Yes, my images look real, and very often people assume they are photographs I took. That is intentional. I look for realism and coherence with the work I have always done. Believability matters to me because it is part of how I communicate and how viewers connect to the image.

However, there is a strong sense of disappointment or rejection when people realize the images were created with AI. Many immediately devalue the work. They assume the creative act has been taken over by the machine, that the artist is no longer present, and that the image somehow “doesn’t count.”

This is where the real issue and the real controversy lie. My work is not created by a machine. It is created by me, with the help of a machine. AI is not the author — I am. Yet there is a tendency to dismiss AI-created work entirely, to say it has no value. That raises a deeper question: what do we define as art, and what do we choose to value? If a machine is involved, does the work suddenly lose meaning?

Photography and digital art have always involved technological intervention. We accept converting an image to black and white, changing a sky in Photoshop, or adding and removing elements digitally. These practices have long been part of photographic language. But when AI enters the process, there is a sudden rejection, as if the rules have changed.

What I find interesting is that this rejection comes mainly from within the photographic community itself. Other photographers are often the harshest critics. They feel something is being distorted, that work is being stolen, that the medium is being betrayed. I don’t see it that way. What I create is new to me, and I don’t consider it a theft of anyone’s work.

For me, AI is simply one more tool. Nothing more. The responsibility, the vision, and the authorship remain human. And I believe it is important to talk openly about this, because the debate is not really about technology — it is about authorship, value, and how we define creative work today.

At the same time, when working with a tool like AI, transparency is essential. It is important to clearly state that these works are not photographs. I always make that distinction explicit. I label my work and explain how the images were created, making a clear separation between photography and AI-created images. For me, photographs are made with a camera, and images are created with AI — they are two different things. This transparency matters, because it respects the viewer and clarifies authorship rather than hiding it.

Do you think viewers respond emotionally because the images look real, or because they carry the visual grammar of photography we already trust?

In relation to my work, I believe people respond emotionally because I work with universal values. I speak about childhood, old age, pain, suffering, joy, innocence, hope, dream, the eternity of life, and death. These values are part of my universe, and whether I work with photography or with AI, the vision behind the images remains the same.

The emotional response does not come from the image being perfect, from a dramatic sky, or from visual impact alone. It comes from what the image is expressing underneath. People connect to the values the image carries, not to its surface.

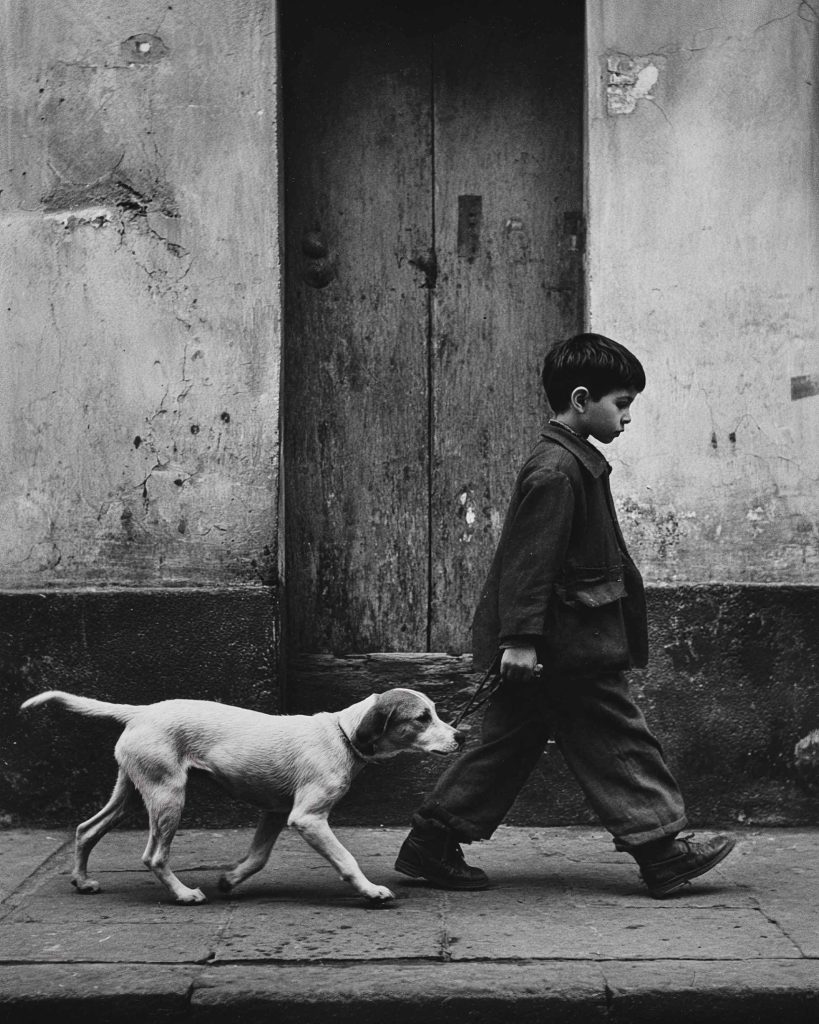

My work is also deeply influenced by humanist photography from the last century. That humanist tradition — focused on humanity, dignity, emotion, and lived experience — plays an important role in how people identify with my images. Viewers are not analyzing composition or technical aspects; they are responding emotionally.

For me, what truly matters is emotion and storytelling. Every image or photograph I create needs to tell a story, to transmit a concept, to carry meaning. Without that, it is just an empty image, deprived of significance.

In an era where “seeing is no longer believing,” what responsibility—if any—do you feel toward the viewer?

We are living in a complicated moment, where AI is often seen as an enemy. In my view, the greatest danger is not AI itself, but the way it is used. Or more precisely, abused.

This tool allows for the creation of works that are extremely unrealistic, fictional, and sometimes absurd. When it is overused without intention or responsibility, it turns into a kind of circus of fantastical creations. That excess undermines the ground for serious, meaningful work and discredits the tool itself. The problem is not the use of AI, but its misuse.

For me, responsibility begins with transparency. It is the creator’s role to clearly state when a work is made with artificial intelligence. The public has the right to know what they are seeing. At the same time, it is also the viewer’s responsibility to be critical and selective about what they believe and consume.

We cannot lead people to believe that something is real when it is not. This question of truth applies far beyond images — it applies to videos, news, and information in general. The careless or manipulative use of AI can have serious consequences, not only at an aesthetic level, but also at social, political, and ethical levels.

That is why I believe the real danger lies in irresponsible use. Transparency, intention, and accountability are essential if we want this tool to be used in a meaningful and honest way.

Ethics & Identity

There’s ongoing debate about AI, originality, and authorship — how do you personally define what makes an image ‘yours’?

What makes an image mine is not the tool that was used to create it, but the vision behind it. My work is defined by intention, by the themes I return to, and by the values I explore. Childhood, memory, innocence, pain, hope, humanity — these are elements that have been present in my work for years, across different mediums.

Whether I work with photography or with AI, the authorship comes from the same place. I make the choices, I define the direction, and I decide what stays and what is rejected. The machine does not have intention — I do.

For me, originality is not about inventing something out of nothing, but about expressing a personal and coherent vision. If that vision is present, the image is mine, regardless of the tool used to bring it into existence.

Do you worry that AI-generated imagery could erode the value of lived photographic experience, or does it make that experience more important than ever?

I don’t believe AI erodes the value of lived photographic experience. On the contrary, I believe it makes it more important than ever.

Henri Cartier-Bresson once said that making photographs is about aligning the heart, the mind, and what we see. That is something I deeply believe in. To be a good artist — in photography or in any other art form — you need to have lived. You need experience. You need to have read, listened to music, suffered, loved, failed, and grown. You need life.

Having life means carrying an inner weight — a collection of experiences, joys, pains, desires, dreams, and aspirations. This personal maturation cannot come out of nowhere. A machine does not have this. It does not have life.

In Portuguese, we say “é preciso ter mundo” — you need to have “world” inside you. That means inner richness, depth, memory, and lived experience. Without that inner world, whatever you create will not move people. It will not touch them, and they will not identify with it. The result will be empty.

AI does not replace lived experience — it exposes its absence. When that inner world exists, it informs the work, regardless of the medium. When it doesn’t, the images feel superficial. That is why I believe lived photographic experience — and lived human experience — remain absolutely essential.

How transparent do you think artists should be about the tools they use, especially when the work mimics traditional photography so closely?

I think transparency is a responsibility. It is not about justifying the tool, but about being honest about the process. When work closely resembles photography, clarity becomes part of the ethical position of the artist.

Transparency builds trust. It allows the viewer to engage with the work without confusion or manipulation. I don’t believe transparency limits interpretation — on the contrary, it creates a more honest space.

For me, being transparent is also a way of taking responsibility for what I create. It acknowledges authorship, intention, and choice. The problem is not the tool itself, but the lack of clarity around its use.

Meaning & Motivation

Why do you choose to make these images — what can AI allow you to express that photography alone could not?

For me, photography has limits — not only conceptual limits, but also very practical ones. Before working with AI, I already had entire projects and collections imagined for photography that I simply could not realize. I didn’t always have the financial means, the locations, the models, or the resources that photographic production often requires.

AI allows me to overcome those limitations. It gives me the possibility to materialize ideas that would otherwise remain unrealized. With this tool, I can finally give form to projects that lived only in my mind. In that sense, AI allows me to transmit and shape my creative dreams in a way that was not always possible before.

If there is something that defines me, it is that I am a project maker. Creativity is the quality I value most in myself. Whether through writing, painting, photography, or digital creation, creativity is the word that best describes how I move through the world. I don’t see myself as an expert in a single discipline. I don’t belong entirely to one art form. But I believe that by working across different forms of expression, I am able to create a coherent and meaningful language.

AI fits naturally into that way of being. It is one more tool in my world, deeply connected to my personal and professional path. I see myself as a multifaceted artist, someone who does not belong to a single medium. That eclecticism reflects my life itself. I have lived in different countries, across different cultures and continents. My life has been fragmented, constantly moving, never fixed in one place.

That fragmented experience is not a weakness — it is what allows me to create something unique. AI gives me the freedom to bring together all those layers — personal, cultural, emotional — into work that feels consistent with who I am and how I have lived.

Looking ahead, do you see this work as a temporary exploration of a new tool, or as the foundation of a long-term artistic identity?

There is something about me as an artist that is both a flaw and a quality: I am deeply curious. I like to experiment with new mediums, new techniques, new languages, and new styles. That is who I am. But I also know myself well enough to say that I can grow tired of things. I tend to move on, to evolve toward something else. Toward what? I don’t know yet.

Because of that, I don’t see this work with AI as a fixed identity. My identity has always been eclectic and fragmented. That fragmentation is a virtue, but also a limitation. I cannot say that I will do this forever — and most likely I won’t. I genuinely don’t know if my path will continue through photography, AI, painting, writing, or something else entirely.

What I do know is that I am a creator. I create out of necessity. That is where I feel at home. I am not good at managing my work, promoting it, or selling it. I struggle with that side of the artistic life. I feel capable of creating, but much less capable when it comes to visibility and structure.

There is, however, a desire behind that. I would like my work to reach people through exhibitions or through a gallery context. I would like that very much. At the same time, I often feel unable to navigate those spaces on my own. Perhaps I only know how to create — and that may be my role.

If one day there were a partnership with someone who could take care of that side of the work, I would welcome it. That is an honest wish. Beyond that, I remain open. Curious. Uncertain. And truthful about not knowing where the path will lead.

Closing

If future audiences encounter your images without context, what do you hope they feel before they question how the image was made?

When someone encounters my images without context, what I hope they feel is not curiosity about the process, but emotion. Comfort. Recognition. A sense that something inside them has been touched or answered, even if only briefly.

My work exists as an attempt to help people. If my work can offer a moment of reflection, reassurance, or emotional response, then it has already fulfilled its purpose. That is why I create. I need my work to have meaning.

As an artist, I create to exorcise my own fears, anxieties, doubts, and perplexities about life and death. These questions accompany me constantly, and creation is the space where I can confront them. Making images is a cathartic act for me. It is where I give form to what troubles me, to what I cannot resolve otherwise.

If someone recognizes themselves in those doubts — if they see their own questions reflected in my work — I feel grateful. Not because the image provides answers, but because it creates a shared space of reflection. If my work can help someone think, feel, or dream, even for a moment, that is enough.

I often receive high appreciation for my photographic work, and this is almost expected or natural. But when people respond emotionally to my AI-created images, the experience feels different because I receive so much negative reactions. So, when someone praises me for my AI work, I am happy: “I know this is AI, but it speaks to me,” or “Even knowing it was created with AI, it moves me,” or “This makes me feel something.” This confirms that the emotion does not come from the tool, but from what the image carries. In those moments, the debate around AI becomes secondary. What remains is the connection.

Authenticity is central to my practice. I try to show who I am through what I create — my fears, my fragility, but also the things that bring me joy. In a time that often feels superficial and performative, this search for authenticity feels increasingly difficult, but also increasingly necessary.

What I hope to create is trust, dream, emotional truth, and connection.

I want my work to tell stories — my story — and through that, to open space for others to reflect on their own.